Essay 13 Marian Reformation

The Essays #13

I believe this is the final paper… every other essay I have from my Bachelor’s degree is either a short paper or a journal. Which means, if I want to continue with this series on the site, I will have to write new papers. How does one balance a fulltime job, a side job, fulltime school, my other blog posts… AND then add in research and writing time for new essays? Did I forget to mention that I also have to get seriously started with writing my novel?

Time management is a problem. But this intro is not doing anything for today’s topic!

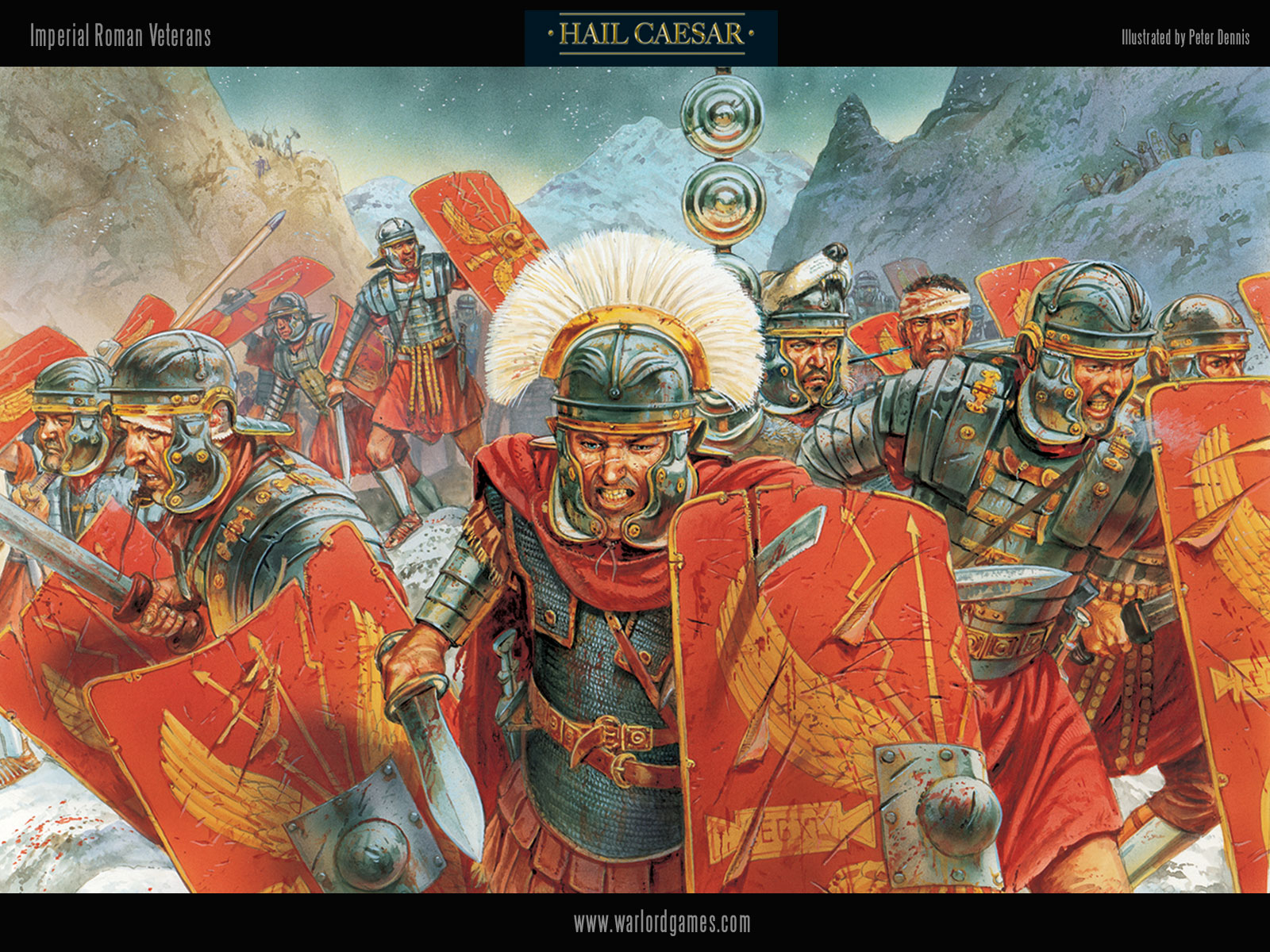

Rome. I have a love of military history, which started from playing role playing games and becoming obsessed with armor and arms, and then becoming a wargamer and becoming obsessed with strategy and tactics. While I started out in Medieval and Dark Age studies, the last few years have seen me delving into the Classics. I have determined that I could probably never be a “real Historian,” as they need to focus on a narrow topic to a deep depth. My interests are far to varied and I just can’t focus.

So, Roman Military.

So, in this short paper I look at the Marian Reformations and project how they are responsible for both the rise of Empire and its fall. I hope you forgive me the sample nature of this post, it was a short paper after all, and merely lays out the facts in a linear fashion.

Domino Effect: How the Marian Reformation was the First

Step to Imperium, and the Fall.

“Domino Effect” might be a slightly hyperbolic title, and an inaccurate analogy. The ultimate fall of Rome would be better likened to the “straw that broke the camel’s back,” as it is numerous changes, reforms, politics, and tribal movements that all added up to a complete mess. However, the Marian Reformation happens centuries before the fall of Rome and it revolutionized the already legendary legions and gave them a resurgence that saved Rome from Gallic invaders and would create Roman domination for the next five centuries.

What are the Marian Reforms? Gaius Marius started as a member of the Equestrian class and managed to maneuver himself into a marriage with a higher-class Patrician woman (he is actually the great uncle of Julius Caesar thru marriage). Marius was elected Consul in 107 BC and was sent to deal with the Jugurtha War in North Africa. The war had been dragging on due to inept leadership.[1] At the same time, actually starting around 113 BC bands of Germanic tribes were raiding Northern Italy and then moving randomly throughout the republic, settling and then moving and starting various wars. Marius went down to North Africa, reformed the legions, ended the Jugurtha War and then immediately came back north to try out his proven legions on the Germanics. But, again, what were the reforms? The legions where facings many issues, first among them was a manpower shortage and second was a losing streak which was severely affecting morale. The main change to the army to address both of these issues was to leave behind the maniple legion and adopt the cohort.

The original Republican Legion consisted of 30 maniples that were arrayed in three lines of differently armed troops, but the new legion would consist of 10 far larger cohort units in uniform gear and equipment.[2] This deeper and larger unit would help with the morale issues, having more men standing beside and behind you will always improve morale in a battle. However, larger units and uniform equipment when you have a manpower shortage is a larger problem. Pre-Marius, soldiers in the Republic army needed to have enough wealth to pay for their own equipment and they only served for the season and then had to be returned to their homes (and farms). Marius decided to remove the landowner requirements for military service and also instituted a salary for soldiers[3]. Now, joining the army would be a commitment of 6 years, with the ability to be recalled for up to 16 years. They were also issued arms and armor, thus making the legions more uniform, the cost of this equipment was charged to their salary. With the extended service, this allowed Marius to have professional soldiers, who would only get better by drilling and living together. This would revitalize the legions, making them even more dominate as the next centuries would show. But it would also have far-reaching consequences which we will arrive to in a moment. Besides these manpower and deployment changes Marius also made sweeping changes to the gear and logistics/baggage of the legion. He outlawed the soldiers having servants and sent away all of the camp followers. Camp followers used to outnumber the soldiers in many ancient battles. Without the servants, prostitutes, children, and merchants tagging along with the army, Marius was able to improve the marching speed of the legion. Without their servants the soldiers were required to carry their own gear, and each 8-man unit also carried communal gear between them; hand tools, a tent, wooden stakes. Carrying all of this baggage gave the legions the nickname, Marius’ Mules. Other changes were to the gear and equipment of the men, primarily in the legion’s armor, where the lorica segmentata became the norm for the legions. It’s the most iconic and well-known armor in history. The Roman javelin, the Pila, was also augmented; originally the steel shaft was affixed to the wooden heft with 2 or 3 iron rivets, but Marius switched to a two-hole set up, the forward one kept the iron rivet but the rear hole was plugged with wood. The wooden plug would break on impact with the shield of the enemy and thus make the shaft bend so the javelin couldn’t be thrown back[4]. Marius made sure that each soldier carried two of these javelins as he abolished the use of velites. Velites were lightly or unarmored troops who used to run out in front of the republic legions and throw javelins or sling stones at the enemy as a precursor to battle.

So how does creating a professional army lead to Imperium and then the Fall of Rome? Well Marius wanted to create a standing army and in order to do that he needed to make them a professional one. The men needed to be paid. One of the best ways to make money in Rome was to go to war, it was one of the reasons why senators fought to become Consul, the sheer amount of money that could be made from loot and slavery. Calling on farmers to fulfill the military needs of the republic engendered an army which existed for the state. But paying these troops, and taking them to war where they could earn shares of the booty, shares that were distributed by their general and not the state, the soldiers soon became loyal to their generals and not to Rome itself.[5] Within 50 years Julius Caesar would show just how dangerous this could become when he committed genocide across Gaul and then returned to Rome and started a civil war to seize power[6]. This would also be seen before that in the civil war and atrocities performed by Sulla against Marius and Rome.[7] The legions made Imperium possible and later they would be the ones to decide who would be Emperor, or even when an Emperor needed to die. The army would be the main deciding force in Roman politics all the way to Adrianople, arguably the end of the Western Empire, even though it would take another 32 years before the Visigoths captured and took Rome, Adrianople was end of the Legion’s dominance.[8]

Now, there are many arguments that many of the reforms were developed over time and that Marius merely had his name stamped on them. Bell in his lengthy article cites several sources that show prototype cohorts and other generals getting rid of servants and camp followers.[9] Marius gets the ok because he had the clout to get the salary approved, and he made good use of proletariat troops. History and the public also love a winner. Marius went into North Africa and broke the Jugurtha War in short order after years of defeats. He marched his armies back into Rome, re-equipped and added more soldiers, and immediately marched into Gaul. There he broke the Germanic tribes which had killed several legions and were traveling through Gaul and Spain as they pleased. These victories against the enemies that had beaten the Romans for years made Marius so popular he served as Consul for 6 years.[10]

The Marian Reforms reinvigorated the Roman Legion and

improved on what was already a fairly dominate fighting force. Professionalism,

long term service, better weapons and armor, stronger tactics, more cohesive

morale and command. When all combined it would dominate the classical world for

the next 485 years (though that last century wasn’t so good) and it would usher

in the age of Empire. This is also not acknowledging that the Eastern Empire

kept a version of the legion in service until its final fall in the middle of

the 15th century.

Works Cited:

Bell, M. J. V. “Tactical Reform in the Roman Republican Army.” Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte 14, no. 4 (1965): 404-22. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.snhu.edu/stable/4434897.

Bishop, M.C., and Coulston. J.C.N. Roman Military Equipment: From the Punic War until the Fall of Rome. 2nd Edition. Oxford and Exeter, Oxbow Books, 2013 (reprint).

Gabriel, Richard A., The Great Armies of Antiquity. Westport, Praeger, 2002.

LENDON, J. E. “SHIELD WALL AND MASK: THE MILITARY PAST IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE.” In Soldiers and Ghosts: A History of Battle in Classical Antiquity, 261-89. Yale University Press, 2005. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.snhu.edu/stable/j.ctt1nptvk.21.

Martin, Thomas A., Ancient Rome: From Romulus to Justinian. New Haven and London, Yale, 2013.

Youtube:

Kings and

Generals. Marian Reforms

and their Military Effect, DOCUMENTARY. Facebook Video Series, 14:19.

Dec. 13, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UIRS_PMeVVY

[1] Thomas A Martin, Ancient Rome: From Romulus to Justinian. (New Haven and London, Yale, 2013) p90

[2] MJV Bell. “Tactical Reform in the Roman Republican Army.” Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte 14, no. 4 (1965) p404.

[3] Martin, Rome, p92

[4] M.C. Bishop and J.C.N. Coulston. Roman Military Equipment: From the Punic War until the Fall of Rome. 2nd Edition. (Oxford and Exeter, Oxbow Books, 2013)

[5] Martin, Rome, p93

[6] Martin, Rome, p101-3

[7] Martin, Rome, p94

[8] Martin, Rome, p196

[9] MJV Bell. “Tactical Reform” p404-422

[10] Martin, Rome, p90